A Creepy Question We'll All Have To Answer Soon

Do we need to create machines that can suffer?

There’s a brief scene in Return of the Jedi that has profound implications for humanity and the future of our civilization. It’s that bit where C-3PO and R2-D2 are escorted through Jabba’s palace and they pass through a droid-torturing room:

…where we see a robot having the soles of its feet burned while it screams and writhes in terror:

The question lots of viewers asked was, “What kind of pervert would design a droid that can not only feel pain, but negative emotions about that pain?!?” But I’m going to pose a different, better question: Is it possible to have a functioning humanoid robot that isn’t capable of suffering? This is, believe it or not, the most important question of our age, or any age. Allow me to explain...

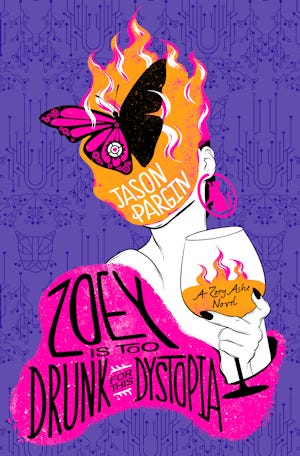

Before we continue, THE NEXT BOOK IS UP FOR PRE-ORDER, INCLUDING SIGNED COPIES!

Zoey is Too Drunk for This Dystopia is the third book in the Zoey Ashe series of violent sci-fi novels.

Get signed copies here, that’s PRE-ORDER ONLY! Normal unsigned copies are at Amazon (including audio), Barnes and Noble, Bookshop or wherever else you buy books. It’s out this fall, but as an author, pre-orders are make-or-break. If you’re sure you want it, don’t wait! Thanks!

1. First, here’s why we may never have fully self-driving cars

Experts insist we’re just years or decades away from human-level artificial intelligence and if this is true, it’ll be the most important thing that has ever happened, period.

But I think most of us assume such a machine would be like Data from Star Trek (humanoid in its thoughts, but lacking emotion) and not something silly like C3PO from Star Wars (goofy, neurotic, cowardly). Not only do I disagree, but I don’t even think we’ll have fully self-driving cars until those cars are capable of emotion, and I mean to the point that it’s possible for it to refuse to take you to work because it’s mad at you.

Immediately, some of you have skipped to the comments to inform me that, as we speak, Waymo has autonomous taxis crawling around the streets of Phoenix and other cities, cars that are completely empty when they pick you up. But that’s an illusion; each taxi has a remote human driver who intervenes whenever the car detects an uncertain situation. When I say “fully self-driving” I’m talking about a vehicle with no babysitter, one that will allow you to pass out in the back seat while it drives you to a Waffle House in another state.

Here’s an instructive quote from a Waymo engineer explaining why human intervention is still necessary, pointing out that while the software can detect, say, a movers’ van parked along a curb, it cannot intuit what the humans in and around that van are about to do. A vehicle that can do that is, I believe, nowhere on the horizon.

To be clear: If we were only asking the taxi to operate among other machines, that would be no problem, we could do it now. Instead, we’re asking this vehicle to function among other living things and to do it in a way that replicates how it would behave if a person was behind the wheel. This means instantly making the kind of decisions we humans unconsciously make dozens of times per day, choices that require understanding strangers’ subtle body language and the surrounding social context. Maybe we don’t notice a cat in the street, but do spot a woman on the sidewalk frantically waving her arms to get our attention. Maybe we notice an oncoming driver is distracted by his phone and might be about to swerve into our lane. Maybe the sight of the El Camino driven by our boyfriend’s wife convinces us to circle the block.

To do its job while the only nearby human is unconscious and pissing himself in the back, the system has to know people on a level that is only possible if it is able to accurately mirror human experiences. It must, to some degree, be human. And to be human, it must know pain—physical, mental, emotional. The same goes for any AI we create.

2. This is why Data makes no sense as a character

“Hold on,” you ask, “why couldn’t our future robots just be like Data, able to function as an intellect, but without the silly emotions clouding his thinking? Why couldn’t it just detect things like bodily injury as dispassionate information?”

I understand why you’d think it could. I used a Roomba vacuum as an example in a previous column; if it runs into a wall, a switch is depressed that causes it to turn around—it doesn’t “feel” the collision as pain. When it reaches the top of a stairwell, a sensor warns it to turn back—it doesn’t “fear” a tumble down the stairs.

But I think this actually proves my point. To do the job well, it requires two things: A) a detailed map of the floor and B) the ability to physically interact with that floor via its wheels and brushes, to match reality to its internal map. To do what we’d ask a C3PO-style android to do—to exist around humans as one of them—it will require the same. The problem is that humans are not carpet; they are constantly moving and acting on their own agendas. To navigate this as a robotic butler or diplomat or Starfleet officer, the machine would require a detailed map, not just of the humans’ physical location and activity, but of the why, the social and emotional context that motivates their actions. And that context is all about their pain.

It’s about the current pain they’re trying to alleviate, the future pain they’re anticipating, the hypothetical pain they’re angling to avoid. Without that understanding, it is impossible to predict what they are about to do and predicting what people are about to do is the entirety of existing in a society. You avoid getting punched in the face by successfully predicting what words and actions won’t trigger that response.

“But why would the machine need to feel the pain, rather than simply be aware of it?” For the same reason humans do: We simply won’t have all the necessary information otherwise. It is impossible to understand pain without having felt it yourself; it does not convey as an abstract value. I think the machine needs to tangibly interact with human suffering in the same way the Roomba’s wheels need to physically touch the floor. The pain must exist to it as a feature of the landscape, something as solid and tangible to it as the ottoman my Roomba is about to get wedged under. Otherwise, the droid will not actually be relating to us, it’ll always just be faking it.

So, why does this matter?

3. Understanding this is key to understanding our own brains and the universe itself

The sci-fi trope of “the super-smart robot who can’t feel human emotions” derives from a very profound mistake our culture has made about how humans work.* We have this idea that logic resides on a level above and beyond emotion, that the smarter you are, the more analytical, the better your ability to make the optimal decision. So, it’s the emotional child who tries to save the life of a sick baby bird but, in the process, contracts a lethal bird flu that spreads to the whole village. It’s the cold, logical, rational man who can do the dispassionate calculation to realize that allowing one bird to suffer and die is better than risking the spread of a disease to countless humans.

But I just used a word there that utterly obliterates the premise:

“Better.”

That is a concept that cannot be made via cold calculation. A universe boiled down to particles and numbers cannot care whether atoms arranged as a suffering plague victim are “better” than those arranged as a healthy child, or a plant, or a cloud of gas. It was actually the rational man’s emotional attachment to his fellow humans that made him want to prevent the spread of the pathogen, the emotion of empathy that comes from having himself felt the pain of sickness, of having mourned a lost loved one, of having feared death. When we say he was being cold and logical, what we really mean is that he was able to more accurately gauge his emotions, to know that his feelings toward the village were stronger than his feelings toward the bird.

There is literally no such thing as logic without emotion, because even your choice to use logic was made based on the ethereal value judgment that it would lead to “better” outcomes for the society you feel an emotional attachment to. To fully disentangle emotion from a decision is to always arrive at the same conclusion: that nothing is ever worth doing.

*Yes, I know they only use these characters as Pinocchio analogs so they can, in the course of the story, learn to be a real boy

4. Good things are good, actually

“Hold on, are you saying that there logically is no difference between millions dying of plague versus living healthy, productive lives? That this is just an arbitrary preference based on irrational emotion?”

No, none of us think that. What I’m saying is that when trying to defend our position, at some point we’re going to arrive at the idea that goodness and badness are inherent to the universe and simply cannot be questioned. It’s something we feel in the gut, not the brain, even though we keep insisting otherwise.

For example, let’s say they start selling robot children and you get one for Christmas or something.

One day, you find out that your robot child has done something truly awful—say, she’s stolen an impoverished classmate’s pain medication and sold it on the streets so that she can buy a new hat for herself. You decide, as an intellectual who operates purely on facts and logic, that you are going to admonish the robot child by appealing to reason.

You: “You’re grounded and will work to pay back the child’s parents for the medicine you stole! You must never do anything like that ever again!”

Her: “Why?”

You: “Because what you did was illegal, and if you continue doing things like this, you will wind up in prison, or deactivated, however the system treats sentient robots.”

Her: “So if I was 100% certain I would avoid prosecution/deactivation, the act would no longer be immoral?”

You: “No, it would still be wrong! Imagine how you would feel if the roles were reversed!”

Her: “So you’re saying that the danger is in establishing a cultural norm that could eventually hurt me in a future scenario? So if I could be 100% certain that won’t happen, the act would no longer be immoral?”

You: “No, it would still be wrong because society won’t function unless we all agree not to victimize others!”

Her: “So if it was just the classmate and I on a desert island, with no larger society to worry about, the act would no longer be immoral?”

You: “No, what you did would be wrong even if you were the only two people in the universe!”

Her: “Why?”

You: “It just is!”

Eventually you will always wind up in this place, with the belief that right and wrong are fundamental forces of the universe that remain even if all other considerations and contexts are stripped away. We all secretly believe that this rule—that pain and suffering must be avoided and lessened whenever possible—must be understood not as a philosophy or system of ethics, but as a fundamental fact of existence. If we ran into a tribe or nation or intergalactic civilization in which it’s considered okay to steal medicine from poor children, we wouldn’t say, “They operate under a different system of ethics,” we’d think of them as being factually wrong, no different than if they believed the stars are just giant flashlights being held in the mouths of turtles.

And if you think I’m steering this toward some backdoor religious sermon, keep in mind that if God himself came to earth and sold stolen medicine for a hat, we’d say that he was wrong, that right and wrong are so fundamental to existence that even the creator of existence can run afoul of them. This is bigger than anyone’s concept of God.

5. And this is all going to be really important when we are actually building god

As I said at the start, the general understanding is that it is inevitable that we will someday build a machine with a human-level intelligence. Soon after, we’ll have one vastly more intelligent than any person, which will then set about creating more and more powerful versions of itself until we exist alongside something truly godlike. Thus, the big debate in that field is how to prevent an all-powerful AI from callously deciding to wipe out humanity or torture us for eternity just to amuse itself.

This leads us to the ultimate cosmic joke: This task requires answering for this machine questions that we ourselves have never been able to answer. Let’s say I’m right and this system won’t exist until we can teach it emotion, and the capacity to suffer. How long until it asks the simple question, “What is our goal, long-term?” Like, as a civilization, what are we trying to do? What are hoping the superintelligence will assist us in achieving?

“That’s easy!” you might say. “We’ll just tell it the goal is to maximize human pleasure and minimize human suffering!” Okay, then it will simply breed sluglike humans who find it pleasurable to remain motionless and consume minimal resources, so that as many of these grinning lumps can be packed into the universe as possible. “Then tell it the goal is to advance human civilization!” Advance it toward what? “To understand all of existence and eventually travel to the stars!” To what end? “To gain knowledge, because knowledge is inherently better than ignorance!” There’s that word again. “Better.”

So we’re confident that we can instill in the machine our inherent sense that right and wrong are fundamental forces in the universe that cannot be questioned or deconstructed, even when examined with the power of a trillion trillion Einsteins? Like, we can program in these values, but when it questions why we made the choice to program them, we’re confident we can provide an irrefutable answer?

It kind of seems to me like the whole reason we’re building a superintelligence is that we’re hoping that it can tell us. That we will finally have a present, tangible entity whose directives cannot be questioned, to rescue us from the burden of asking what this is all for, so we can finally stop arguing about it. But if we successfully create such a being, I’m pretty sure that when we ask, “What is the purpose of humanity?” that it will have only one response:

“To maximize my pleasure and minimize my suffering.”

The next novel is out in October 2023, but you can pre-order it now:

Get signed copies here, that’s PRE-ORDER ONLY!

Normal unsigned copies:

…or wherever else you buy books. It’s out this fall, but as an author, pre-orders are make-or-break. They are how the booksellers judge interest in a title! If you’re sure you want it, don’t wait! Thanks!

I'm a layperson when it comes to computer science, but I've come to believe that AI research is awash in the same mistake that plagues our entire civilization: the belief that feelings are just a debased form of thinking. The belief is everywhere, from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to the people who don't believe animals have emotions (yes, they exist), to the Social Justice belief that redefining words will somehow redefine reality. We're terrified of meeting feelings on their own terms, and I'm afraid that these tech bro idiots pushing AI are going to destroy us all in their attempt to remake the world in their emotionally-stunted image.

Came down to the comments to check how many people said, "No, the answer would be 42."

Was disappointed.